A History of Claremont in 100 Objects: Surfboard-Mary Garner Hirsch Collection #4 "Surfboard"

A History of Claremont in 100 Objects: Surfboard-Mary Garner Hirsch Collection

#4 "Surfboard"

Artifact Description: Balsa wood surfboard in canvas, approximately four feet long and two feet wide, located in the Garner House; child’s bedroom.

Walking through Claremont, one doesn’t have to look to hard to see surfboards. On the tops of people’s cars, you can find a veritable array of different boards with different graphics and colors, each a sort of factional marking; a statement that the owner is a true Californian. At my home institution, Pomona College, there is an Outdoor Educational Center where students can borrow surfboards, boogie boards, and wetsuits for weekend trips to the beach; it is expected that some students will seek the coast and California’s breaks. The Surfboard is such an indistinguishable part of Southern Californian Culture that it almost is impossible to imagine the landscape without it. But hidden inside surfboards is a historic story, one with many different narrative threads and many different lessons.

The artifact I’m discussing today is a surfboard that belonged to the Garner Family. Part of the Mary Garner-Hirsch Collection, this surfboard was used by the sons of Herman and Bess Garner.

Modern surfboards are typically made of fiberglass resin, epoxy, and ultra-lightweight materials. However traditionally they were made from hollow and light wood, such as teakwood or balsa wood. Surfboards came in a variety of shapes, sizes and forms. The three-fin design of more contemporary boards emerged as a result of an exchange between board makers in California, Australia and in Hawaii who synthesized a blend of board making techniques providing for stability, form, and function. The small size of the Garner’s board would fit comfortably in the category of papa li‘i li‘ or small surfboard, the forerunner to modern bodyboards. (Warren and Gibson, 2014.)

Surfing, is an ancient tradition. In their book, Waves of Resistance, Isaiah Walker traces the history of surfing from Hawaii to Tahiti, across Polynesia across thousands of years. The modern form of surfing as we know it first emerged 1500 years ago. Among Hawaiian society and culture, surfing was not just a recreational practice, but also an equalizing, democratizing one, open to all regardless of sex or gender. It was also tied to spiritually significant practices; prayers were often recited on surfboards, and offerings were frequently made to bring waves. Many chiefs were also deified and recorded in legend on the virtue of their ability to surf. (Walker, 2011.)

The first Europeans to witness surfing were part of the Cook expedition of 1778. Arriving on the shores of Maui, Captain Cook’s expedition included several observations of surfing: “Upon this they get astride with their legs, then laying their breasts upon it, they paddle with their hands and steer with their feet, and gain such Way thro’ the Water, that they would fairly go round the best going Boats we had in the two ships, in spight of every Exertion of the Crew, in the space of a very few Minutes.” (Eschner, 2017.)

Captain Cook was the first European to make contact with the Hawaiian islands. He and his crew were also among the first Europeans to witness and record surfing.

The British sailors who encountered the native Hawaiians imported with them European sensibilities and understandings. As Walker describes, European sailors understood female Hawaiian surfers to be masculine, and brutish. Later, when American Calvinist missionaries arrived in the 1820s, they quickly became concerned about the effect that surfing had on the morals of native Hawaiians. One of the first missionaries, Hiram Bingham the 1st wrote that surfing encouraged “sexual behavior.” A commonly misunderstood myth is that these Calvinists banned surfing and that surfing effectively went extinct in the 19th century. This is not however the case. Surfing was practiced all the way through the 1800s and into the 20th century whereupon it was introduced to the California Coast by several prominent native Hawaiians including George Freeth. In fact, in the 1860s Samuel Clements, also known as Mark Twain, attempted to learn the sport upon observing his Hawaiian guides engaging in surfing. In his travelogue Roughing It, Twain describes his experience attempting to surf: “I tried surf-bathing once, subsequently, but made a failure of it, I got the board placed right, and at the right moment too; but missed the connection myself. None but natives ever master the art of surf-bathing thoroughly.” (Clements, 1872.)

The erosion of the practice of surfing in Hawaii was more complex than an outright ban by American Missionaries. Until the overthrow of Queen Lili’uokalani in 1893, Hawaii was itself a sovereign nation with its own government. The issue of surfing was divisive amongst missionaries, some of whom participated in surfing and considered the practice to be good for the mind and body. But missionaries did not have the power to ban the practice of surfing, either as a part of Hawaiian life, or as a sport, and while they did write extensively either about the virtues or the scruples of surfing, surfing persisted. Instead, surfing and the erosion of the practice amongst native Hawaiians was completed in an imagined understanding of the ownership of surfing, through the appropriation of the sport by White Americans, and through the gradual erasure of indigenous sovereignty and ownership over the Hawaiian Islands. Californian and Australian surfers began to be credited with having “revived” the sport in the 1940s and 50s, but in truth the practice never died to begin with.

Queen Liliʻuokalani was the last Queen of Hawaii before she was removed in a coup-d'état led by Sanford Dole, patriarch of the Dole Corporation over sugar taxes. Dole established a Hawaiian Republic with the intent of annexation by the United States for more favorable trade conditions and for more direct control of the native labor force. In a counter coup against the Republic, many of her supporters were arrested and imprisoned, including Liliʻuokalani herself. She died in 1917, spending more than two decades attempting to gain recompense from the US in its illegal annexation of sovereign Hawaii.

This has led to what Walker describes as two separate surf cultures, one imagined in the view of non-Hawaiians or Haole, and one continued by Hawaiians as part of an ancient living tradition. The construction of these two separate traditions of surfing was made through movies, and music, like the 1958 film Gidget, and Elvis Presly’s Blue Hawaii. Perhaps most recognizable however are the Beach Boys, from Hawthorne California, a band whose name itself came from the Waikiki Beach Boys, including Duke Kahanamoku who like George Freeth introduced the art of surfing to non-Hawaiians who came to the Moana Hotel. (Fowler, 2013.) The music and movies of the 50s and 60s created a romantic view of surfing, a care-free lifestyle of surf, sand, and sun that promised a kind of eternal youth that fit in perfectly with the mythos of California as a garden paradise.

The historic Moana Hotel on Waikiki beach was where many Americans were first introduced to surfing.

This transformation of the nature of surfing as well as its cultural ownership vis-à-vis the popular imagining of surfing culture continued to be nestled against the craft of surfboards themselves. As surfboards became a commercialized product, the art of hand-crafted surfboards became a kind of resistance for indigenous artisans. Some Haole surfers also continued to make boards in defiance of what they saw as a commodification of a space that abhorred business and capital. Still, the market for surfboards continued in what Andrew Warren and Chris Gibson described as “exporting Hawaii.”

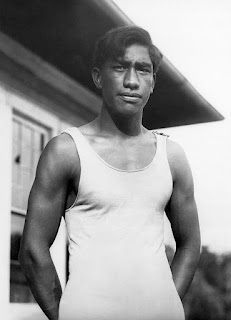

Duke Kahanamoku was a Hawaiian two time Olympic gold medalist, an actor, and renowned surfer. He introduced surfing to many Americans and popularized it as a recreational activity and sport. PBS named Kahanamoku one of their American Masters, and the University of Hawaii's swimming and water polo center bears his name in recognition of contributions to Hawaii and for his abilities as an athlete.

The conflict between ownership of surfing in some ways burgeoned out into actual physical violence between surfers over territory. In California rival surf gangs that emerged in the 1970s fought to enforce their rights to specific stretches of beach, to claim the best surfs for surfing. The tensions between these gangs often mirrored ethnic and racial tensions. Even in modern times the phenomenon sometimes persists. Police in Palos Verdes and El Segundo notably struggled with gang violence in Lunda Bay who see outside surfers as threatening the sanctity of what they see as their beach. (Joiner, 2016.) Miki Dora, one of the most infamous figures in Californian surfing culture was known to paint swastikas on his surfboard to intimidate other surfers who were not local to the area. Dora pioneered “localism,” the enforcement of surfing territorial rights to local surfers only and encouraged an elitist attitude that looked down on beginners and outsiders. (Duane, 2019.) These cases are not examples that we point to contradict the self-described identity of surfers, but to instead highlight the complexity of understanding what surfing culture exerts, and the complicated relationship between surfing and ownership entails.

For many Americans, the Beach Boys (top to bottom: Brian Wilson, Carl Wilson, Dennis Wilson, David Marks, Mike Love) popularized the imagery of surfing culture and created the idea of the archetypical surfer. Their early songs and music cultivated the fantastical life of the California surfer, living day-to-day traveling from beach to beach.

In any case, surfing remains and continues to grow as an immensely popular recreational activity, one that has been exported globally. In California, surfing is a uniquely central part of the imagery of the state and its culture. But like so many other aspects about California, surfing is a borrowed tradition adapted and reformed into something new. As thousands of Californians take to the beach each day, the question for us now is who owns surfing? Should we not consider surfing a shared element of our daily lives that belongs to everyone? What other elements of California’s daily landscape are found elsewhere?

Acknowledgements:

A History of Claremont in 100 Objects is a blog series presented by Claremont Heritage and written and contributed to by its members. Based on the podcast A History of the World in 100 objects by the BBC and the British Museum, presented by former British Museum director Neil MacGregor. A History of Claremont in 100 Objects explores Claremont history through its material cultural legacies, placing objects important to the history and development of Claremont in larger relation to US and World History.

About the author:

My name is Cooper Crane. I am an archival intern with Claremont Heritage. I study history and anthropology with an emphasis on archaeology and the history of empire and environmental history at Pomona College in Claremont. I was born in Anaheim and have lived my whole life in Corona California, a city with a similar shared history to Claremont. I have degrees in history, anthropology and political science from Norco College California and am a certified California Climate Steward through the University of California Department of Natural and Agricultural Resources. I write to explore history through the material objects of history, and by exploring the elements of history that are unwritten. My current work at Claremont Heritage includes the curation of artifacts on display at the Garner House and the Claremont Packing House, the creation of artifact descriptions for our archives and contributing to A History of Claremont in 100 Objects.

Citations:

Duane, D. (2019). The long strange tale of California’s surf nazis. The New York Times. Opinion | The Long, Strange Tale of California’s Surf Nazis - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Eschner, K. (2017.) What the first European to visit Hawaii thought about surfers. Smithsonian Magazine. What the First European to Visit Hawaii Thought About Surfers | Smart News| Smithsonian Magazine

Fowler, T. W. (2013). The Waikiki beach boys…. A look back. Aloha Surf Guide. The Waikiki Beach Boys….A Look Back | Aloha Surf Guide

Fox, C. T. (2018). How Waikiki’s legendary beach boys defined aloha. Hawai’i Magazine. How Waikīkī's Legendary Beach Boys Defined Aloha - Hawaii Magazine

Joiner, J. (2016). In California, old school and newbie surfers are clashing. National Geographic. Lunada Bay Bad Boys Fight for Control of the Beach (nationalgeographic.com)

Walker, I. (2011). Waves of Resistance: Surfing and History in Twentieth-Century Hawai’i. University of Hawaii Press.

Warren, A and Gibson, C. (2014). Surfing Places, Surfboard Makers: Craft, Creativity and Cultural Heritage in Hawai’i, California, and Australia. University of Hawaii Press.

Comments

Post a Comment